- Nine hours of Hiaki-language interviews with elders, transcribed and translated in full.

- Interviews conducted between 1969-2008 by Ms. Maria Florez Leyva, with Hiaki elders who personally experienced warfare, deportation and exile from their homeland at the hands of the Mexican government in the early to mid 1900s.

- To appear as a volume from University of Arizona press, titled Au te waate: We remember it.

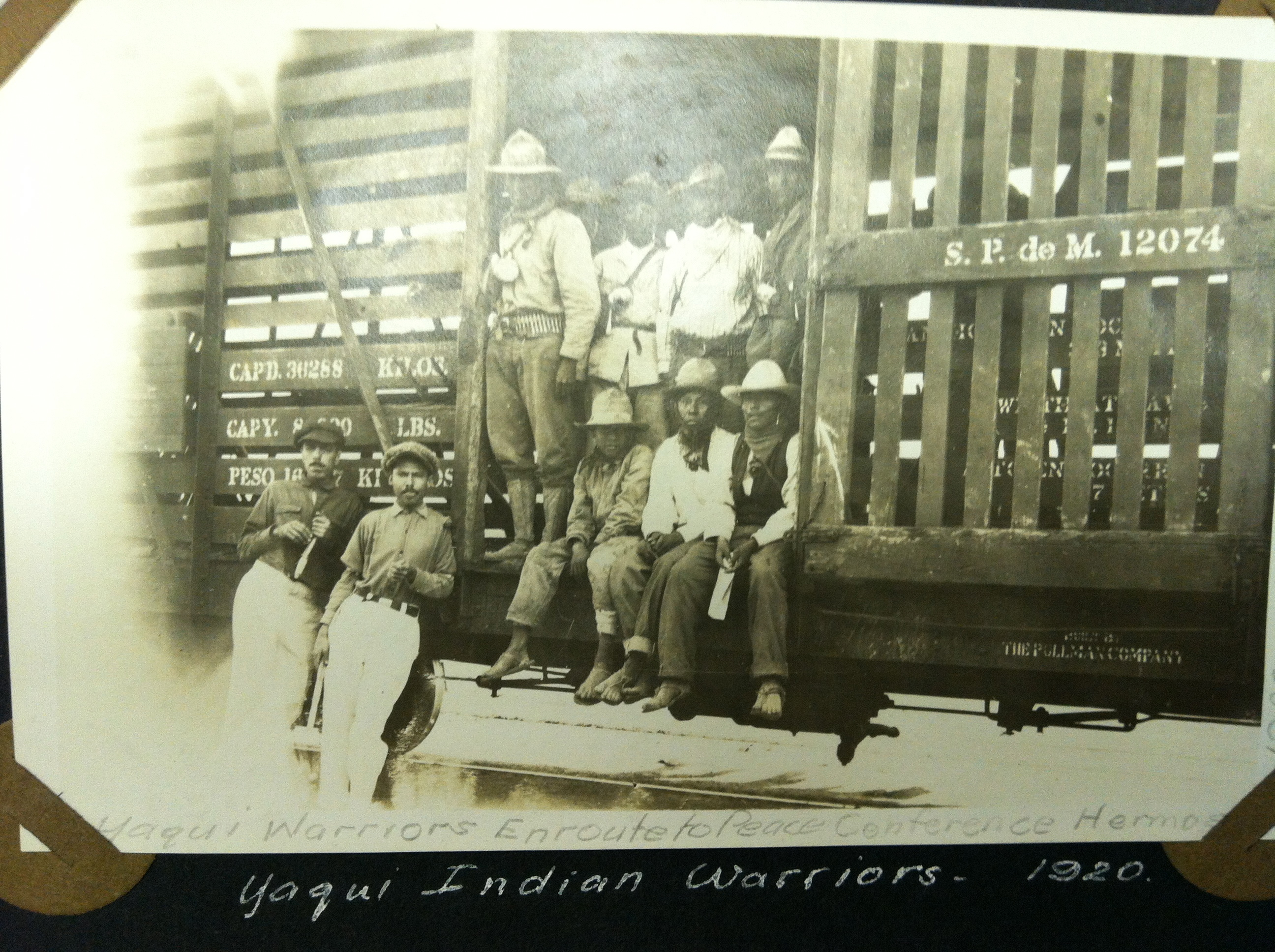

The Mexican revolution from 1910-1920 saw the beginning of an increased migration of people from Mexico to the southwestern part of the U.S., including Arizona. The Hiaki people also joined in this movement out of Mexico, which is referred to as the “Great Dispersal” or “ Yaqui Diaspora” (Spicer 1974:7).

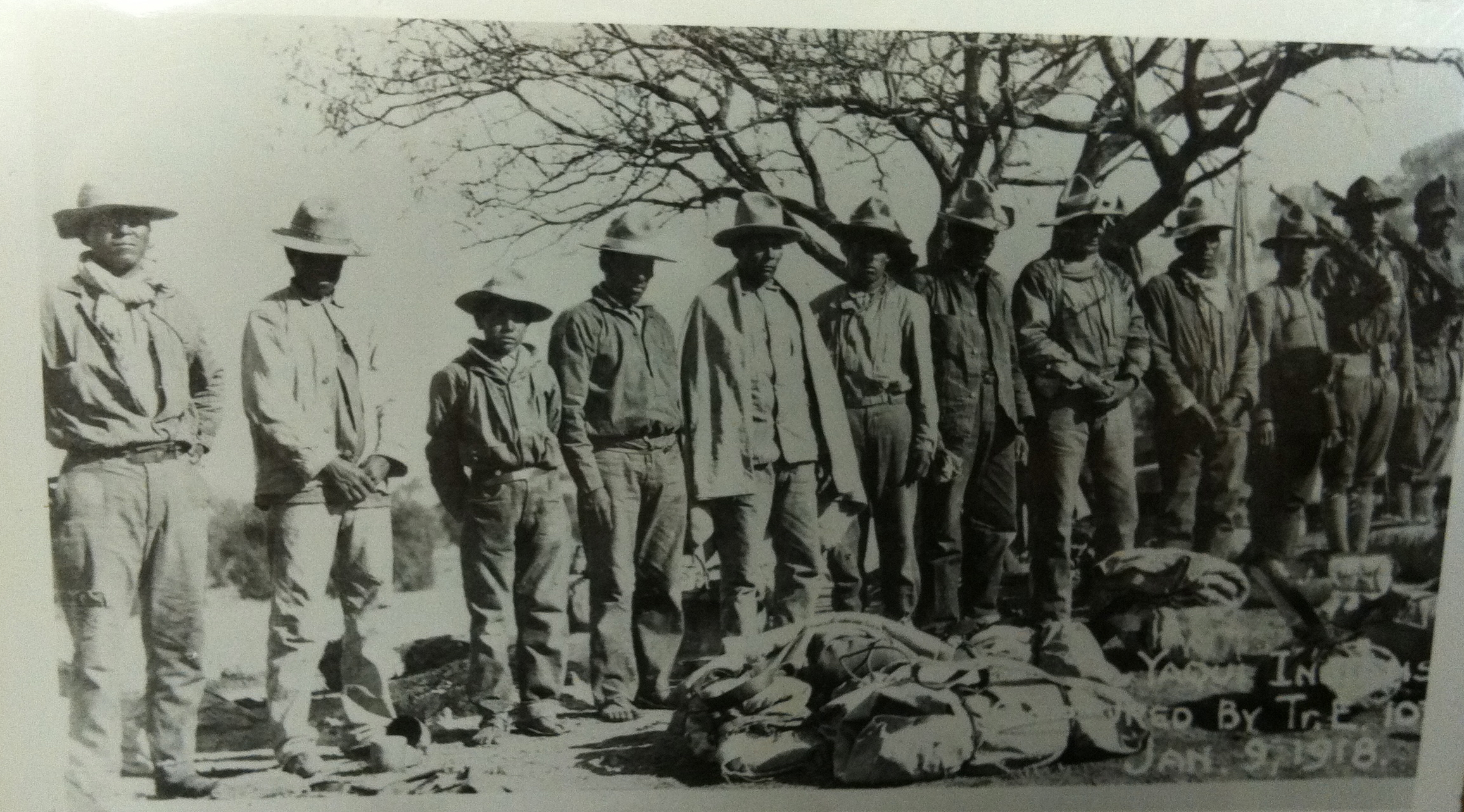

This occurred because during and after the war, the Hiaki communities were being attacked by the Mexican military, and deported from their homeland in Sonora, Mexico. They were taken to Yucatan to work in forced labor camps on plantations. Many families and communities were torn apart.

Many Hiaki people escaped to Arizona. Here they worked on ranches and in mines for very low salaries. The Mexican government wanted the U.S and Arizona authorities to control the border crossing of the Hiaki and also to find and deport the Hiakis back from where their Diaspora led them. Many employers did not cooperate, however, because Hiaki labor was cheap and very much needed. The refugees often passed as members of other tribes or as Mexicans in order to not get deported.

In other cases, Hiaki refugees escaped to mountainous regions in Mexico, inland from the more coastal Hiaki pueblos. This was the situation of one family of a lady who was interviewed, named Maria Luisa Buitimea, known as Doña Luisa. A transcript of part of Mrs. Leyva’s interview with Doña Luisa can be found below.

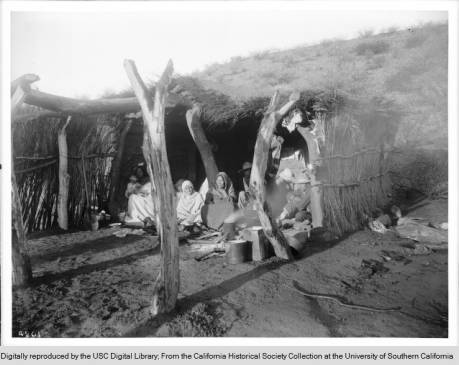

In the interview file available below, Doña Luisa and her family talked about their experiences during this time of displacement. Doña Luisa described the scarcity of food and water that they encountered.

They would have to travel a long way down the mountain just to get water and would sometimes have to eat plant shrubs and desert shrub roots to survive (p 5-6, p 36). They would huddle around a small fire in order to stay warm, which they had to start by rubbing sticks together (p 7-8), and build tents out of sheets to stay dry from the rain.

Mothers would give birth and apply a pinch of dirt to the umbilical cord (p 4). She explained the long 3- 4 month walking journey that she and her family took when they escaped (p 51). She described several disturbing experiences, such as ambushes of the Hiaki people which ended in the murder of children and adults, and the mutilation and desecration of corpses by the attackers (p 38). Anyone who was found to be helping the mountain Hiakis was punished severely (p 49).

Doña Luisa expressed the determination of the Hiakis to maintain their independence as follows:

Kaa au nenenka, kia hakwo huni’i. Es de que hunuen haksa suawa, hain chu’um venasi suawa. Hain hikau wiikwa, vem usimmak chukti malaka susuawa, ta kaa emo nenenka. Hiva emo defendiaroa.

They never surrendered, never, they were killed everywhere and killed like dogs. Even when they were lynched and children, mothers were killed, still did not they surrender. They defended themselves.

This shows the strong mindset that the Hiaki people had, which took them through this time of hardship while maintaining their independence and identity as a people, despite the terrible cost.

References

Levya, Maria. Interview with Dona Luisa. University of Arizona. June 10,2010

Spicer, Edward H. Yaquis and Federal Indian Policy: From immigrants to Native Americans. Journal of Southwest. December 22,2002.

Maria Florez Leyva, can be contacted at: mfleyva@email.arizona.edu